Why Governance of AI Matters

Artificial intelligence is no longer a future prospect—it is already reshaping productivity, business models, and societal structures. Yet the scale, speed, and complexity of these changes often overwhelm our capacity to direct them towards good. We know that AI solutions will be key in achieving the global goals. But we also know that it brings new risks and challenges. The central question is no longer whether to govern AI, but how to do so in ways that balance innovation, inclusion, and long-term societal benefit.

International organizations, governments, businesses, and civil society face a core tension: how to advance AI as a driver of innovation, economic growth and security while mitigating its risks. Without aligned standards and safeguards, AI applications in healthcare, education, or sustainability may also deepen bias, inequality, and mistrust. This is not a technological failure, but an institutional one.

In this article we explore two examples and draw lessons for the future of AI. First, past experiences in internet governance—particularly the multistakeholder model developed over decades—offer guidance. Institutions like the ITU have shown how collaborative processes can produce standards, norms, and oversight that respond to complex technological shifts. Second, healthcare, offers a particularly instructive case: it combines high public sensitivity, complex data flows, and a wide range of actors with competing mandates. The following section explores possible ways forward, by examining how governance structures shape power and legitimacy in practice

Centralization vs. Decentralization

AI governance is being shaped under conditions very different from those that guided the internet’s early development. The internet grew out of decentralized principles: open protocols, distributed technical communities, and arenas like the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) where governments, firms, and civil society engage on relatively equal terms. By contrast, AI today is defined by concentration. A handful of firms and state-backed actors control the compute, data, and talent required to set the pace of development.

This difference matters because governance structures crystallize power relations. If the future of AI is steered primarily by a few dominant players, global governance risks becoming fragmented and unbalanced. Unilateral initiatives may advance quickly but undermine legitimacy, while multistakeholder efforts risk tokenism if they lack real authority. The São Paulo Guidelines, endorsed at NetMundial+10 in 2024, were a recent attempt to set principles for multistakeholder cooperation. Yet geopolitical tensions are affecting consensus, leaving broad and inclusive efforts like these vulnerable to being sidelined. The lesson for AI is clear: without durable mechanisms of shared stewardship, governance will either entrench inequality or collapse under competing pressures. These challenges invite us to look at traditions where diverse actors have successfully worked together to shape common rules.

Multi-Stakeholder Governance Traditions

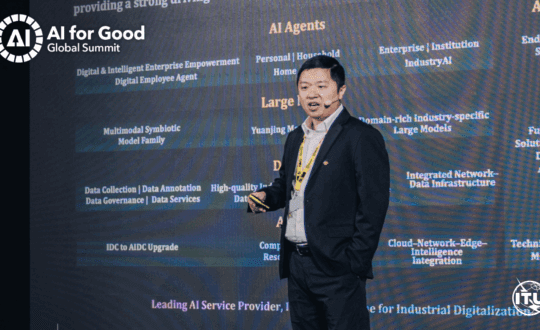

With 20, and more, years of experience, the internet governance setup offers useful lessons in how different governance traditions can be combined. The World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), which shared the space during the yearly AI for Good Global Summit, did not produce binding laws, yet it influenced global priorities by convening diverse actors into a deliberative space. While the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), on the other hand, exercises executive authority over technical coordination. Taken together, these examples show the value of layering deliberative forums with executive bodies, where spaces for dialogue shape agendas and institutions implement concrete decisions.

Yet multistakeholder platforms are never free of tension. Inclusivity can slow processes down while efficiency can sideline important voices. Even mundane details—such as who speaks, how interventions are summarized, or how meetings are structured—carry weight. But the key lesson is that legitimacy does not come from formal authority alone. It comes from sustaining workable compromises across heterogeneous actors. For AI, this means building a governance arena that is at once open and decisive: forums to debate priorities broadly, and institutions capable of translating those priorities into action while guarding against capture by powerful interests.

Why Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships Matter (the Case of Health)

Healthcare is one of the clearest domains where AI governance cannot be left to a single actor. Health systems are inherently interdependent: patients, clinicians, regulators, hospitals, researchers, and technology providers all influence outcomes. Decisions around data, algorithms, or care delivery directly affect lives, rights, and trust. In this context, governance must reflect the perspectives and responsibilities of all actors involved.

As digital tools become central to diagnosis, treatment, planning, and surveillance, critical questions emerge: Who controls the data? How are decisions made? What values guide the system? No single institution can answer these alone. Governments have legitimacy but often lack technical agility. Tech companies bring innovation but are not democratically accountable. Hospitals understand patient needs but don’t set global standards. And patients, while most affected, have historically had little voice. Multistakeholder governance is therefore essential—not optional.

The European Health Data Space (EHDS) exemplifies this approach. It seeks to enable both primary (care) and secondary (research, innovation, policy) uses of health data through a federated, trust-based model. Patients retain data control, regulators ensure safeguards, technical experts ensure interoperability, and governance is shared across the ecosystem. This approach is being operationalised through TEHDAS2 (Towards the European Health Data Space), a Joint Action involving 25+ countries. Through structured workstreams and consultations, TEHDAS2 develops practical governance mechanisms. Its core message: legitimacy is not declared—it is earned, by treating each stakeholder as essential.

Three key lessons emerge:

- Shared responsibility builds legitimacy. Inclusive systems earn trust. Exclusion leads to resistance and failure.

- Aligned incentives prevent fragmentation. TEHDAS2 shows how transparent, consensus-driven processes can bridge diverse goals.

- Coordination prevents capture. Neutral forums—like those in internet governance—are essential to ensure AI in health serves collective, not concentrated, interests.

Murillo Salvador serves as the Geneva Hub Leader for the Young AI Leaders community at AI for Good, where he works to create meaningful connections between young innovators and Geneva’s international ecosystem. His vision centres on harnessing AI’s potential to catalyse new forms of collaboration and collective action in addressing global challenges.

Alongside this role, Murillo is pursuing doctoral research at the University of Geneva’s Department of Sociology. His research examines how international organizations harness multistakeholder platforms and public communication activities to facilitate global cooperation around emerging technologies, with a special focus on artificial intelligence.

Drawing from his professional experience in communications and stakeholder engagement at international bodies including the OECD, Murillo is passionate about building bridges between academic research and practical implementation. As a teaching assistant at the University of Geneva and web culture expert at poliScope – the University’s platform for secondary schools – he brings valuable experience in mentoring young people and translating complex situations into actionable projects.

As a member of the AI for Good Young AI Leaders community, he aims to promote an environment where young pioneers can develop action-oriented capacities that align with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Holds a Master’s in Multidisciplinary Research, biophysics, and a Bachelor’s in Biotechnology, with extensive studies in bioinformatics and data science, and experience in healthcare innovation and entrepreneurship. Fluent in 7 languages, with 4 at native level. Adam started his career in biophysics, and later founded his first startup MidasTimes to help improve mental health of students, and later joined Luci Health where he achieved the position of COO.

Now board member of the Institute for Human Centered Health Innovation and ElevateHealth, Adam also serves as advisor for the e-Health Innovation Center and director of innovation and scientific programs of the International e-Health Forum. Adam also serves as president of Innovation Forum in Barcelona and consultant, associated expert and/or advisor in local and international private and public organizations in healthcare (Boehringer Ingelheim, EIT Health, Evidenze, Fundación Visible. Digital Mental Health Consortium). Recognized for leadership in healthcare innovation and global health discussions, his work has received more than 15 million impressions. Adam is also currently member of the Global Shapers Longevity Economy Task Force organized by the World Economic Forum.

During his career he has recieved training from some of the best institutions companies, universities, and accelerators/incubators, such as KTH, Johnson & Johnson, CIMTI, Health Inc, Innovation Forum, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Ghent University, Pompeu Fabra University, and Banco Santander.