Artificial intelligence could help fight climate change, or quietly make it worse. That paradox framed the session “AI and Climate Change: Balancing Innovation and Sustainability,” held on the Centre Stage at the AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva from 8 to 11 July 2025. Dr. Sasha Luccioni 🦋, AI and Climate Lead at Hugging Face, challenged the audience to look beyond the simple narrative of AI as hero or villain and to confront its full environmental footprint.

Luccioni described how conversations around AI and sustainability “often a dichotomy… a binary distinction between AI that hurts the climate and AI that helps the climate.” Their talk aimed to bridge that divide, showing how AI can drive breakthroughs in renewable energy and conservation, even as its own development consumes vast amounts of electricity, water and rare minerals.

Hugging Face, an open-source AI platform that hosts “millions of open source models,” sits at the centre of this tension. Luccioni’s work focuses on reducing AI’s environmental footprint while applying it to sustainability challenges.

“The way I like to see AI in fighting climate change is from different levels,” Luccioni said, “from the micro level of molecules all the way up to the macro level of satellites, and of course our level, the biodiversity level, the human level.”

At the microscopic level, AI is proving an unlikely ally in materials science. Algorithms trained on vast chemical datasets can identify new compounds for batteries and solar panels, offering alternatives to lithium-ion technologies. Luccioni noted that such breakthroughs could “completely change the game when it comes to electrifying our grids.” Better batteries, they argued, are essential for decarbonising power systems and integrating renewables at scale.

Further up the chain, AI is helping biologists track and protect ecosystems. In one project cited by Luccioni, Rainforest Connection repurposes old mobile phones fitted with solar panels and AI models to monitor sounds deep in the Amazon. When the devices detect chainsaws or trucks, alerts are sent to rangers combating illegal logging “using the power of AI”. Camera traps now use similar systems to recognise individual animals by their markings, zebra stripes, for instance, allowing conservationists to monitor populations across vast areas without continuous fieldwork.

Image from Sasha Luccioni’s presentation

At the planetary level, satellite data and AI models are being combined to reveal patterns invisible to the human eye. Luccioni described how infrared analysis can pinpoint methane leaks from melting permafrost, while underwater imaging helps scientists assess coral reefs “through tens or hundreds of metres of water.”

Luccioni has spent years building bridges between AI researchers and climate scientists through the nonprofit Climate Change AI, launched to help specialists in ecology, physics and chemistry adopt machine-learning tools. But optimism, they warned, must be tempered by realism. “There’s no free lunch,” Luccioni said. Every digital process carries an environmental cost.

Data centres already consume vast amounts of power, accounting for as much as a quarter of total electricity use in some U.S. states. The surge in energy demand is compounded by the water required to cool servers, often drawn from regions already facing scarcity. In the United States alone, Luccioni noted, “25% of a state’s energy is used by data centres,” with emissions “rising quite drastically in recent years because of AI.” The environmental cost of what is commonly referred to as the cloud is now estimated to exceed that of the airline industry. Yet expanding renewable capacity takes years, Luccioni warned, while “AI doesn’t give us that time.”

Training large language models (LLMs) is particularly resource-intensive. A study by Luccioni estimated that training OpenAI’s GPT-3 emitted around 500 tonnes of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of 500 transatlantic flights between New York and London. Subsequent models, such as BLOOM, achieved a twentyfold reduction by using renewable energy, yet the underlying problem remains: model sizes and energy needs continue to grow.

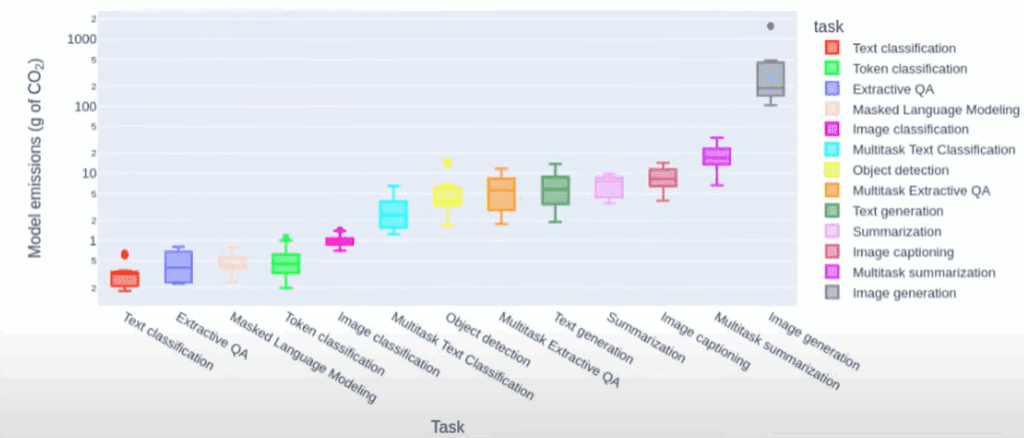

Even after training, emissions persist. In a follow-up study titled Power Hungry Processing, Luccioni lead a study measured the energy used in deploying AI systems. Each individual query may consume a trivial amount of power, but the scale of global use, millions of image generations and chatbot prompts, translates into substantial aggregate demand. “Each query might be a small amount of energy,” Luccioni explained, “but if everyone is generating Ghibli selfies […] or cute pictures of kittens, then this really adds up.”

Image from Sasha Luccioni’s presentation

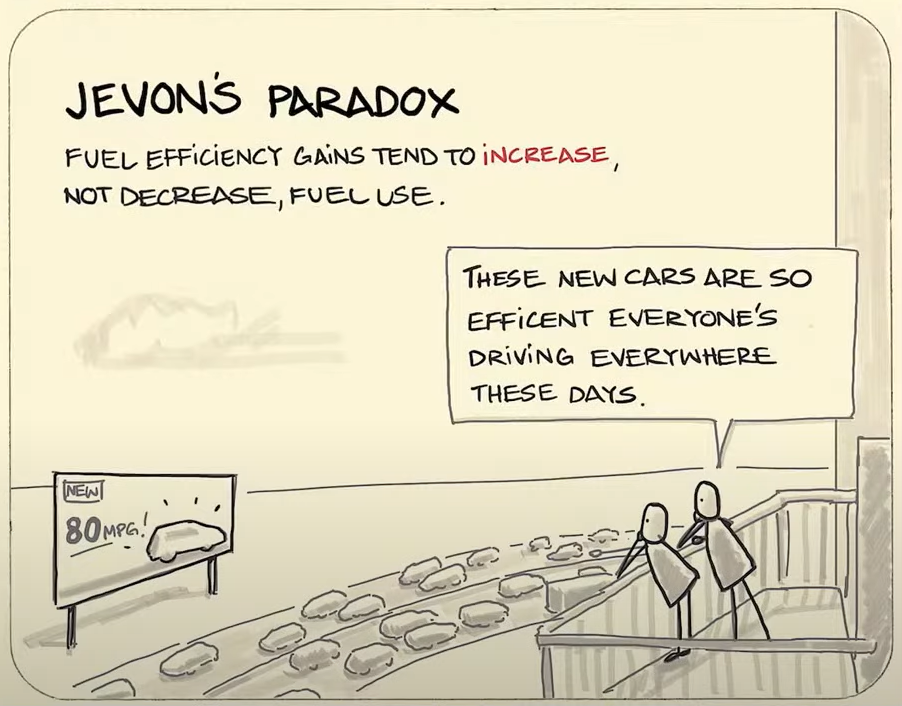

Beyond these measurable costs lie what Luccioni calls “butterfly effects”, indirect consequences that extend through material culture, economics and society (read the research paper). The shift from paper maps to digital may seem efficient, yet the data centres that store our maps, recipes and archives are far from dematerialised. Another subtle consequence is what economists term the time rebound: time saved through automation is often reinvested in other consumption-heavy activities, offsetting environmental gains.

The phenomenon echoes Jevons’s paradox, first observed in the 19th century, which holds that “when technological progress increases the with which a resource is used”. From coal to cars, the more efficient we are at using a resource, the more we end up using it.

Image from Sasha Luccioni’s presentation

“Despite the fact that technological efficiency is going up, the amount of the resource being used is also going up. So it’s a paradox, because it should be going down” said Luccioni.

Faster, cheaper computation encourages greater AI adoption, fuelling new demand. “We are truly seeing this Jevons paradox of AI” Luccioni stated “and changing the power dynamic of our field [academic field]”. As the cost of training climbs into the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, academic researchers increasingly depend on industry partners, raising concerns about independence in the field.

Advertising provides another feedback loop. AI systems optimise targeting with uncanny precision, stimulating consumption. “AI makes us buy things we wouldn’t have bought otherwise,” Luccioni noted, pointing to a contradiction at the heart of the digital economy: the same algorithms that track deforestation and coral reefs also drive the online commerce contributing to environmental strain.

For Luccioni, acknowledging these contradictions is not a call for rejection but for responsibility. “AI is not a silver bullet,” Luccioni concluded, “but it has potential.” The challenge, then, is one of discipline: matching technological ambition with ecological restraint. That requires transparency about energy use, greater reliance on renewable sources, and more conscious choices by users and institutions. Everyday decisions, whether to query a chatbot for a recipe or use a simple calculator, accumulate into real planetary costs.

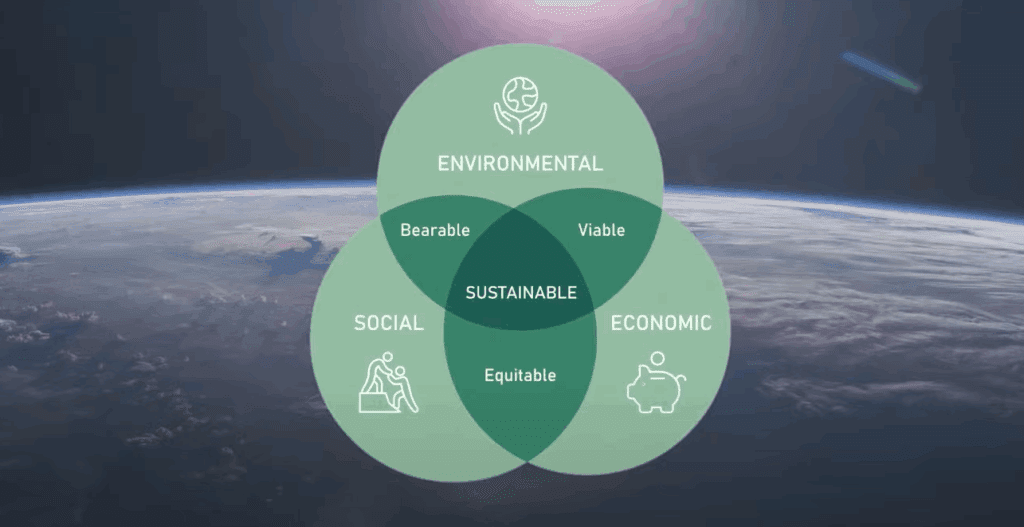

In the end, Luccioni returned to a familiar framework: sustainability’s three pillars, environmental, social and economic.

“If we’re focusing on either of these three pillars, we’re missing the big picture,” Luccioni said. “For AI to be truly sustainable, AI has to respect social justice, respect economic incentives and respect the environment.”

Image from Sasha Luccioni’s presentation

Want to watch the full session?

The replay is scheduled for the 23 December 2025: Register now >