At a time when people around the world are observing social distancing measures to halt the spread of the global COVID-19 pandemic, driverless mobility – which, by definition, offers mobility with minimal human interaction – seems more relevant than ever.

Yet, as developers and researchers around the world have suspended real-world testing of their autonomous vehicle fleets due to health concerns amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it appears we are still a long way from a fully autonomous future.

Barriers to deployment

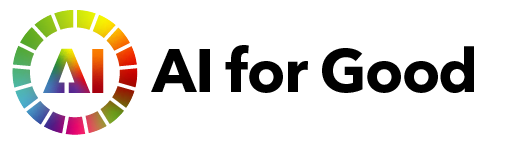

“2020 was billed as ‘Prime Time’ for the self-driving car industry, so where are the self-driving cars and trucks we were promised?” Bryn Balcombe, Chief Strategy Officer at Roborace and Founder of the Autonomous Drivers Alliance (ADA), asked as he moderated the fifth episode of the AI for Good webinar series on COVID-19: Where are the self-driving cars and trucks?

“I think we need clarity on regulation globally …” — Michelle Avary, World Economic Forum

The discussion looked at what barriers remain for autonomous vehicle deployment and how the future of self-driving vehicles may be reshaped following the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the panellists, Michelle Avary, Head of Automotive and Autonomous Mobility at the World Economic Forum, pointed to three core stumbling blocks that autonomous vehicles face today.

“I think we need clarity on regulation globally – without a doubt, that’s needed. But we also need technological validity, as well as business model validity,” she said.

Slow moving deliveries – a potential business model?

A driverless future is often mentioned in the same breath as increased road safety, hailed as a means to reduce the 1.35 million global road fatalities every year.

But in the wake of the current pandemic, we need to expand the definition of “safety” in the automotive sphere to include different types of safety such as biosafety, said Avary.

The panellists agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted a core business case for autonomous vehicle deployment within the logistics and delivery space — certainly in the near-term.

“What we saw coming out of China in using non-contact, low-speed, highly-automated vehicles for delivery in areas that were locked down, we really should explore more of these and think about where we can remove some of the biosafety risks to our essential workers,” said Avary.

And as the global pandemic continues, the companies that can pivot to this slow-speed delivery of goods, such as groceries or medicine “have the best chance of surviving,” said panellist Missy Cummings, Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Duke Pratt School of Engineering, United States.

“I think that the COVID-19 scenario is going to really decimate the driverless car community,” she said. “Those companies that survive will be the ones that figure out that the delivery slow-speed operations is the right way to go in the near-term.”

Despite current trends away from public transport systems – notably in China, which has seen a dramatic drop in ridership since the easing of the national COVID-19 lockdown – panellists saw this as the first step towards mass autonomous transit systems in the longer-term, as a way to meet current biosafety standards (i.e. social distancing measures) and address ongoing trends in on-demand transport.

Global collaboration for safer roads

But before this can become a reality, both for the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, the driverless future faces safety issues of another kind: perception.

“There’s still a problem with prediction in terms of predicting the behavior of all the other road users and I think that’s actually something that will be coming to the fore as we progress in the perception quality system,” said Balcombe.

“You are not going to solve this problem by putting more sensors on a car …” — Missy Cummings, Duke University

While people can understand and predict pedestrian intent, autonomous perception systems – image processing and machine learning probabilistic reasoning algorithms that help autonomous driving systems understand the world around them and act accordingly – are having to make the most reasonable guess about which course of action to take under the circumstances.

“When the system doesn’t perform the same way every time, even under the most benign conditions, then how can we ever put guarantees on its ability to navigate the world safely?” said Cummings.

But it is not just a simple hardware fix, she added. “You are not going to solve this problem by putting more sensors on a car, because until we figure out how to at least replicate in part judgment under uncertainty, all the sensors in the world are not going to solve that problem.”

One way to overcome this issue, suggested Avary, is to establish global minimum safety guidelines for perception systems.

A ‘vision test for cars’?

Additionally, Cummings called for the global autonomous vehicle community to establish “a vision test for cars” to continuously test and validate these technologies.

But any meaningful progress on road safety will rely on global cooperation among the private sector and governments, the participants agreed.

“We really need to make sure that we’re sharing the data in the learning more widely, because we don’t think that every single company and every single operator needs to learn safety first-hand,” said Avary. “There’s plenty of places to compete, but we don’t believe that core safety is one of them.”

So in much the same way that the global community is working together to contain the COVID-19 pandemic through the sharing of best practices in network maintenance and collaborating to ensure #LearningNeverStops, the automotive industry must come together to ensure the safe and steady roll out of autonomous vehicles — and increase road safety in all its forms, agreed participants.